How Ready are Leading Large Language Models for the Draft EU AI Act?

Armageddon is coming!

Stanford’s Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence Institute (HAI) considered how well ten popular AI foundation models comply with the draft European Union AI Act. Nine of the 10 are large language models (LLM), and one is a text-to-image model (Stable Diffusion). The results suggest AI model providers have a lot of work ahead of them. HAI researchers reported:

Foundation models like ChatGPT are transforming society with their remarkable capabilities, serious risks, rapid deployment, unprecedented adoption, and unending controversy. Simultaneously, the European Union (EU) is finalizing its AI Act as the world’s first comprehensive regulation to govern AI, and just yesterday the European Parliament adopted a draft of the Act by a vote of 499 in favor, 28 against, and 93 abstentions. The Act includes explicit obligations for foundation model providers like OpenAI and Google.

…

Foundation model providers rarely disclose adequate information regarding the data, compute, and deployment of their models as well as the key characteristics of the models themselves. In particular, foundation model providers generally do not comply with draft requirements to describe the use of copyrighted training data, the hardware used and emissions produced in training, and how they evaluate and test models.

Grading AI Model Compliance

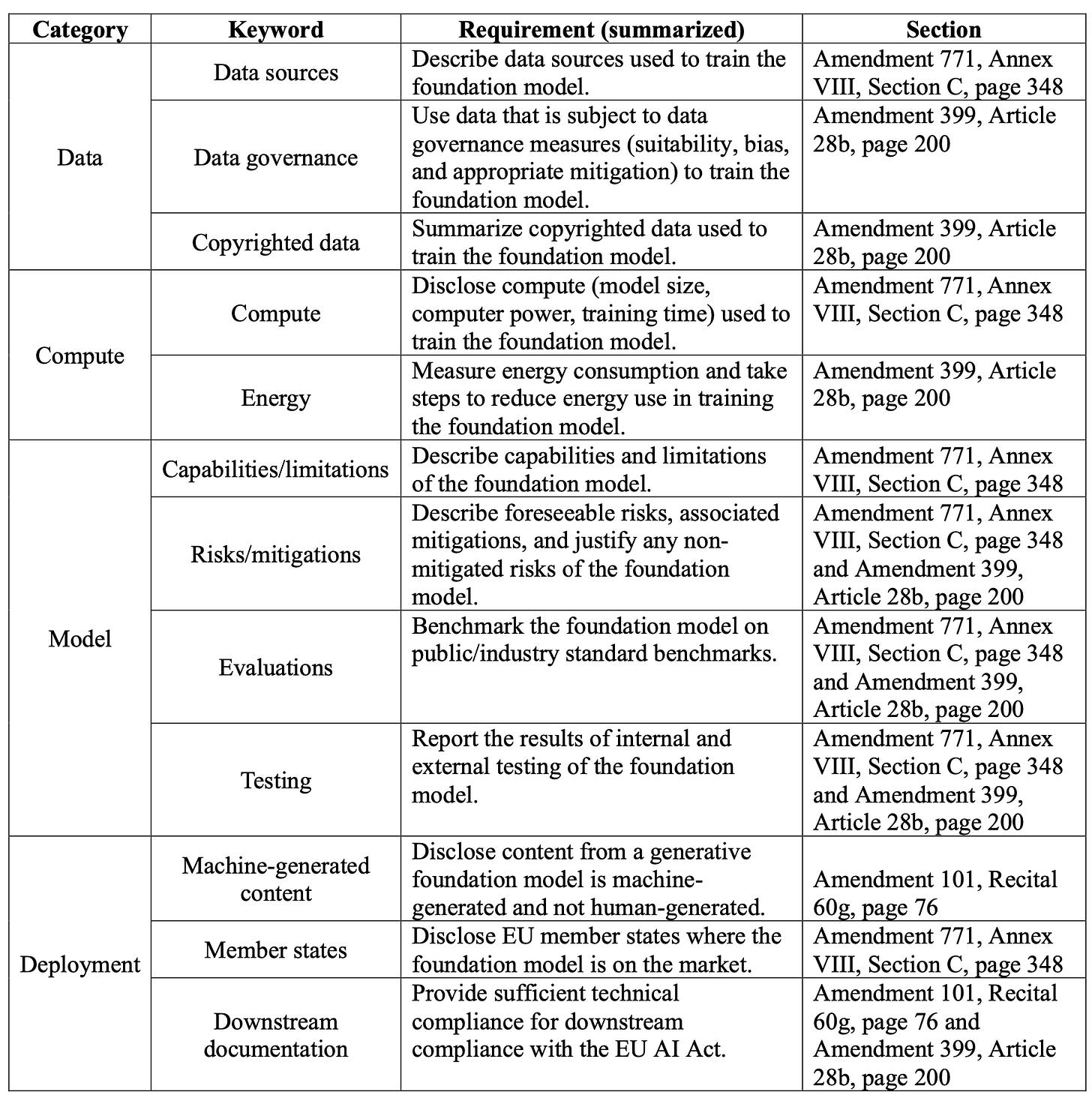

The HAI team reviewed the draft legislation and identified 22 unique requirements (see table below), and selected 12 that they could reasonably assess. These were assigned to four categories:

Data - information about the model training data

Compute - information about the computing inputs used to train models

Model - information about the model performance and risks

Deployment - operational details about model use in production

They then applied a 5-point rubric (i.e., 0, 1, 2, 3, 4) to assign the estimated level of compliance. This resulted in a total potential score of 48.

A couple of items are worth noting. First, the requirements are about disclosure. They are not about function, performance, or output results. There may be other requirements in these categories, but they were not discussed.

Second, Stanford did not grade 10 of the compliance requirements due to a lack of meaningful information. It is likely that the estimated compliance scope coverage is less than what is reported.

Third, a rating of 0, 1, 2, or 3 could be presumed non-compliant for a particular requirement. Legal compliance is generally binary. You are in compliance, or you are not.

This would also suggest the estimated compliance scope coverage is overly optimistic. Model ratings below a score of 4 imply the amount of work a company must do to become compliant. A score of 3 could be interpreted that the model provider already provided 75% of what it needs for full compliance. That company only needs to do the last 25% of the work, while a score of zero means they have not even started.

Fourth, there is no differentiation between the level of effort, complexity, or practicality of any of these draft requirements. So, moving from a 3 (partially compliant) to a 4 (fully compliant) in one category could actually be harder than moving from a 0 to a 4 in another category.

With this context in mind, let’s look at HAI’s analysis.

How the Models Stack Up

Hugging Face’s BLOOM scored 36 out of a potential 48 points. You might think that is 75% compliant. However, only five of the 12 requirements are viewed as fully compliant. This suggests BLOOM is compliant with less than half of the requirements.

BLOOM is an open-source large language model. GPT-NeoX is also open source, and it received the second-highest overall score of 29 and showed full compliance in four requirements. The open-source text-to-image model Stable Diffusion v2 also had full compliance in four requirements and an overall score of 22. According to the report:

Open releases [such as BLOOM, Eluther AI’s GPT-NeoX, and Stable Diffusion v2] generally achieve strong scores on resource disclosure requirements (both data and compute), with EleutherAI receiving 19/20 for these categories. However, such open releases make it challenging to monitor or control deployment, with more restricted/closed releases leading to better scores on deployment-related requirements. For instance, Google’s PaLM 2 receives 11/12 for deployment.

This brings up an interesting dilemma. Open-source AI foundation models disclose a great deal about their AI models, but their distribution approach means they exert little control over their use. If someone uses BLOOM or Stable Diffusion to break the law, are the creators of the open-source generative AI models liable? They may be subject to fines by the EU at a minimum.

This risk could substantially impact the valuations of the AI model creators Hugging Face and Stability AI, respectively, if they must account for future fines. It may also cause some sources of potential funding and prospective customers to avoid these models if EU regulatory actions are deemed likely.

Alternatively, OpenAI and Google are examples of proprietary generative AI model creators. This distribution approach means they can exert significant control over model use. However, they do not want to publicly release significant detail about their technology and enable competitors to easily copy their intellectual property.

This situation led Stanford researchers to conclude that companies such as Hugging Face and OpenAI could, at maximum, achieve 90% compliance given their current business models. Full compliance would require significant changes.

However, the propriety AI model developers may have an easier path to compliance. They simply need to increase transparency in their disclosures. This may introduce competitive risk, but it is feasible.

Open-source developers, by contrast, are unable to exert significant control over the operations of their models by third parties. They often do not know who is using their technology. For their own operations, these requirements are feasible. It is less clear what standard will apply to ensure the models are not misused by others and that those users follow disclosure rules.

To be clear, the Stanford researchers concluded that compliance is feasible.

While progress in each of these areas requires some work, in many cases we believe this work is minimal relative to building and providing the foundation model and should be seen as a prerequisite for being a responsible and reputable model provider.

Unsurprisingly, OpenAI has taken to lobbying for changes to the Act. According to Time:

OpenAI has lobbied for significant elements of the most comprehensive AI legislation in the world—the E.U.’s AI Act—to be watered down in ways that would reduce the regulatory burden on the company, according to documents about OpenAI’s engagement with E.U. … In several cases, OpenAI proposed amendments that were later made to the final text of the E.U. law.

…

In 2022, OpenAI repeatedly argued to European officials that the forthcoming AI Act should not consider its general purpose AI systems—including GPT-3, the precursor to ChatGPT, and the image generator Dall-E 2—to be “high risk,” a designation that would subject them to stringent legal requirements including transparency, traceability, and human oversight.

The EU Law Will Set the Standard

The EU AI Act still must go through the Trilogue process, where further changes will likely be made before the rules become law. However, it is unlikely that the requirements will be watered down enough to make compliance easily within reach of any generative AI model developer. Substantial change will be required for companies expecting to do business in EU member nations.

This task may be particularly significant for companies such as Anthropic and AI21 Labs. These are high-profile LLM developers that placed in the bottom three of the Stanford evaluation. The gulf between their current practices and compliance are more significant than all but one other AI model developer.

Regardless, the EU plans to wrap up the Trilogue process in late 2023, with rules going into effect as early as 2024. The scope of the EU legislation and its status in final negotiations between the governmental bodies means that it is likely to set the global standard for AI regulation by default.

The EU is the world’s third-largest economy. Most companies will want access to the market. That means they will figure out a way to comply and try to ensure more stringent rules are not imposed elsewhere. This is what happened with GDPR, and the EU AI Act looks like Europe’s second turn as the tech world’s regulator.

Don't Miss the Generative AI Innovation Showcase - Synthedia 3 Online Conference

Synthedia 3 is an online conference showcasing generative AI demos, new features, and insights from innovators shaping today's most significant technology segment. The conference is free, but you must register to attend or to get early access to the video recordings post-event. And it is next week!

Thank you, Bret. Key building blocks for all to study.