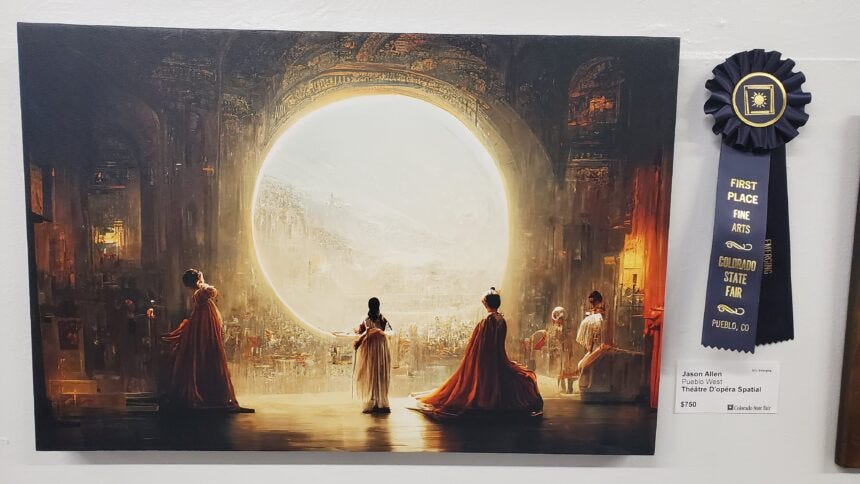

Midjourney Wins Art Contest

Is clever prompt creation art?

Jason Allen won first place in this year’s Colorado State Fair fine art competition in the Digital Arts/Digitally Manipulated Photography category. The meaningful details are that the artwork titled Theater D’opéra Spatial won first prize and the artwork was created primarily with Midjourney. According to the Washington Post, Allen also used “Adobe Photoshop to remove visual artifacts.” Also, Allen is a game developer that doesn’t consider himself an artist.

We wrote a couple of days before this story broke in this newsletter that AI-image generation was having a moment. That moment just became a lot bigger. An obscure art contest at a 150-year-old state fair just became part of art history. AI-generated art— synthetic media conceived by a human — just beat humans in a human-judged competition.

Was it the AI or the Artist

This has led to widespread claims of cheating on social media. However, the judges of the art competition and even the third-place finisher don’t believe any rules were violated. Per the Washington Post:

“One of the judges, Dagny McKinley, an author and art historian … said she did not realize the art was AI-generated but said it wouldn’t have changed her judgment anyway; Allen, she said, “had a concept and a vision he brought to reality, and it’s really a beautiful piece…

“No one has filed an official grievance over the result, either, department spokeswoman Olga Robak said, though there has been an unrelated dispute in the fair’s goat-shearing contest.

“Robak, who studied art history, finds the controversy fascinating. ‘People put bananas on the wall and called it art,’ she said. ‘Even photography was not considered an art form for a long time; people said it was just pushing a button, and now we realize it’s about composition, color, light. Who are we to say that AI is not the same way?’”

Allen told the Washington Post that AI “is a tool, just like the paintbrush is a tool.”

Not the First High Profile Use of AI-Art

Algorithmic art has been sold in fine art auctions at Sotheby’s and Christie’s. In those instances, the computer was the brush, and the artist needed to write, or get someone else to write, the code.

Anne Spalter, a widely recognized artist, sold a collection of 501 spaceships as NFT art pieces in June. The software Night Cafe was her brush. She, like Allen, needed to write the prompt that guided the AI as to what she wanted. The prompt may be more accessible to people because you don’t need special training other than to understand English. Is this really that much different than writing code?

In fact, there is a long history of famous artists using apprentices to produce the actual artwork. The artist brought the vision and the curation and maybe some refinements, but most of the work was done by someone else. Many artists were no doubt frustrated by that approach and the famous artist appropriating the work of others. There is a long-running debate in the art world about these topics.

Democratizing Art Creation?

However, this is not the end of the story. Everyone familiar with these tools seems to recognize that devising the prompts for AI-image generators is a creative process in its own right. You have to have a vision for what you want to see and craft precise statements to get the system to generate what you would like. Allen says he created hundreds of versions and spent at least 80 hours on the project.

Then again, you might not even need to do that anymore. PromptBase is a new marketplace for prompts that will help you generate just the type of images you want to see. For a couple of dollars, you can buy a prompt and have a really good idea what will come out. This might make the question of who the originator of the idea behind the artwork even cloudier.

We are early in this process. AI-image generation hasn’t actually had its AGT moment the way deepfakes have just experienced. However, there is now cultural awareness in a way that didn’t exist a week ago.